Gail Shotlander/Getty Images

- The Vikings inhabited Newfoundland 470 years before Columbus landed in North America, research found.

- Scientists previously dated a Viking settlement in Canada to the 11th century.

- But tree-ring dating and astrophysics revealed that Vikings were there in 1021.

History buffs and scientists have long known that a Viking settlement on the northern tip of Newfoundland dates back to at least the 11th century. Today, that spot, called L'Anse aux Meadows, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. But until this week, the exact dates the Vikings inhabited it was a mystery.

Now, thanks to a surprising combination of tree-ring dating and astrophysics, scientists have pinpointed the precise year the Vikings inhabited Newfoundland. It turns out they beat Christopher Columbus' 1492 voyage across the Atlantic by 470 years, according to a paper published this week in the journal Nature.

The Vikings who lived at L'Anse aux Meadows came to Canada from Greenland, marking the first time that Europeans crossed the Atlantic Ocean. It was the first and only Viking outpost in North America outside of Greenland.

"One of the most exciting things about this research is the potential of the method for future studies. The timelines of many early civilizations are still very difficult to pin down, and this offers a way to connect human activity directly to calendar time without the need for written records," Michael Dee, a coauthor of the paper and geoscientist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, told Insider.

Astrophysics and archaeology collide

Petra Doeve/REUTERS

In 1021, exactly 1,000 years ago, the Vikings cut down at least three trees in L'Anse aux Meadows.

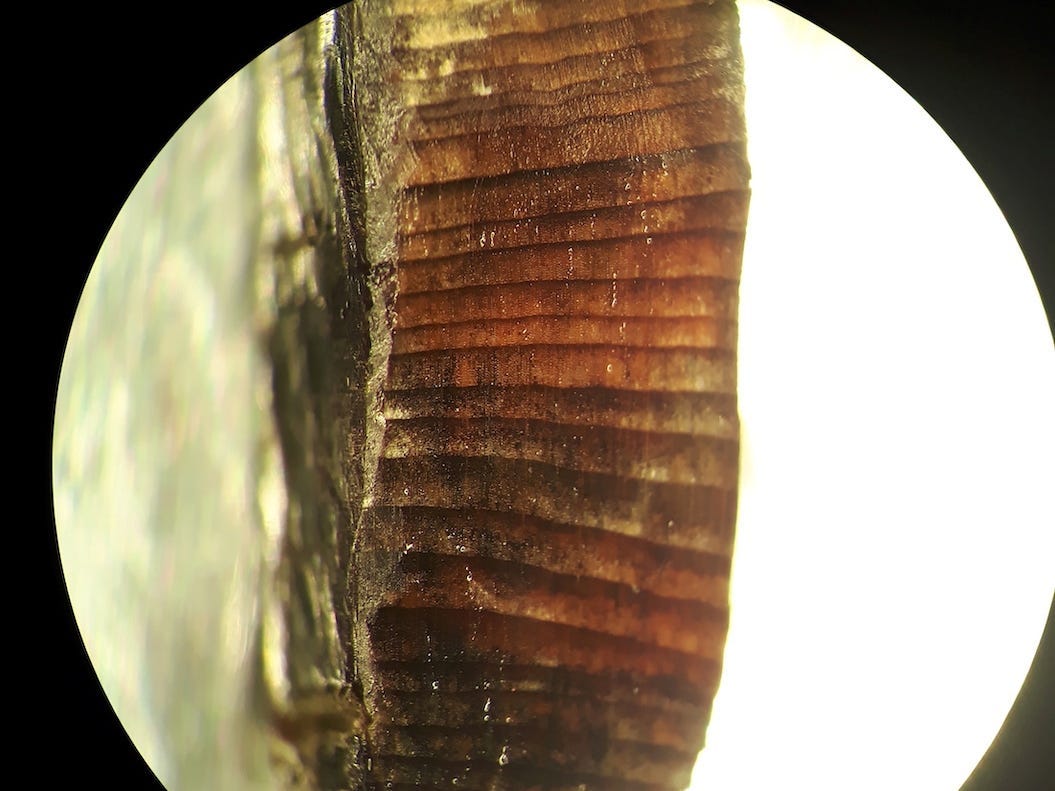

Dee and his teammates pinpointed that precise year by counting the growth rings of pieces of wood from those trees, which were discovered in L'Anse aux Meadows in the 1970s. The wood came from two fir trees and one juniper.

Previous age estimates of the wood were less precise and had been calculated using carbon dating. To complicate matters, indigenous people inhabited the L'Anse aux Meadows settlement both before and after the Vikings did, so made nailing down the precise dates the Vikings arrived was tricky.

But scientists saw that the wood had been cut cleanly with metal tools, and the local indigenous people were not manufacturing metal tools at the time the trees were felled.

REUTERS

So the researchers turned to a relatively novel technique for dating wood - using cosmic radiation as a time marker. The researchers were aware that what's known as a cosmic ray event occurred in the year 993. These events are characterized by a surge in the radiocarbon concentration in the atmosphere, possibly caused by a large solar storm.

So trees that were alive in 993 have evidence of radiocarbon in their growth rings from that cosmic ray event.

Such events, though, are exceedingly rare: "At the moment, we only have three or four in all of the last 10,000 years," Dee told The New York Times.

So it was easier to narrow the timeline from there. Once the researchers had established the radiocarbon marker in the wood, they counted the rings after that, until they reached the bark. When the bark edge is present in a wood sample, the paper explains, "it becomes possible to determine the exact felling year of the tree."

That's how the team determined the year the Vikings ended the trees' growth by chopping them down - and confirmed that they lived in Canada at that time.

Having a precise date for the Vikings' occupation of Newfoundland is crucial to understanding their history, the researchers point out in the paper.

"More importantly, it acts as a new point-of-reference for European cognizance of the Americas, and the earliest known year by which human migration had encircled the planet," Dee and his coauthors wrote.